sydney opera house

The story of probably the most iconic building in Australia is one interspersed with architectural perfectionism, engineering genius, political tug of wars, and an architect who left before his work was done, never to return again to Australia.

The Sydney Opera House is undoubtedly the building of the 20th century.

The Sydney Opera House is undoubtedly the building of the 20th century.

utzon's winning design

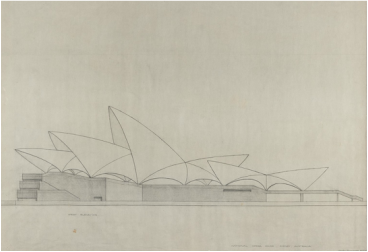

Utzon's original design with a much 'flatter' shellwork

Utzon's original design with a much 'flatter' shellwork

In 1955, Joe Cahill, NSW Premier, announced an international design competition of an opera house.

The building was to be placed prominently on Bennelong Point, the east bank of Sydney Cove, which had previously served as a tram depot. Jørn Utzon's entry, one of the last to be received, was selected as the winning design.

It was a bold, visionary and complex design with two theatres next to each other on a large podium covered by interlocking ‘shells’. In their Assessors’ Report, the judges explained their choice of Utzon’s design

The building was to be placed prominently on Bennelong Point, the east bank of Sydney Cove, which had previously served as a tram depot. Jørn Utzon's entry, one of the last to be received, was selected as the winning design.

It was a bold, visionary and complex design with two theatres next to each other on a large podium covered by interlocking ‘shells’. In their Assessors’ Report, the judges explained their choice of Utzon’s design

We have returned again and again to the study of these drawings and are convinced that they present a concept of an Opera House which is capable of becoming one of the great buildings of the world…Because of its very originality, it is clearly a controversial design. We are however, absolutely convinced of its merits.

an ever-changing design

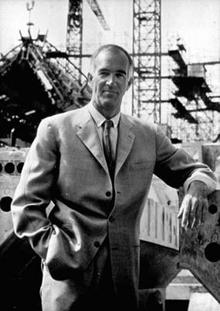

Utzon in front of the construction site

Utzon in front of the construction site

The project was to be funded by public funds through a lottery raised four times a year. The initial budget for the building was established, not by Utzon or with any thorough engineering input, at AUS $7 million, a huge underestimate of the final figure of AUS $102 million. This gross miscalculation also proved to be a major contributing factor to Utzon’s departure from the project some 11 years later.

Utzon was given responsibility for developing the program but was to be assisted by an engineering company for the complicated vaulting and shellwork. Utzon recommended the company of a fellow Dane, Ove Arup & Partners, with whom he had worked previously.

Over the years, several design changes were made by Utzon in close collaboration with Arup in order to make it structurally sound. Some of the world’s leading engineers and craftsmen were involved particularly in the second stage of constructing the very complex roof, coming up with innovative and groundbreaking techniques.

Utzon was given responsibility for developing the program but was to be assisted by an engineering company for the complicated vaulting and shellwork. Utzon recommended the company of a fellow Dane, Ove Arup & Partners, with whom he had worked previously.

Over the years, several design changes were made by Utzon in close collaboration with Arup in order to make it structurally sound. Some of the world’s leading engineers and craftsmen were involved particularly in the second stage of constructing the very complex roof, coming up with innovative and groundbreaking techniques.

nordic craft vs. cheque-book control

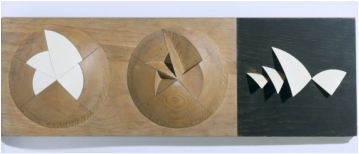

The new design

The new design

However, in 1965, the newly elected Coalition Government took office led by Robert Askin with Davis Hughes as the Minister for Public Works. The election campaign had been dominated by the Opera house project with the winning coalition stressing the need to bring the project back in line and on budget.

A very well documented rift between Utzon and Hughes followed, between the perfectionist and the pragmatist. Utzon’s Nordic craft approach to architecture working closely with other skilled companies who were equally focused on high quality (over cost) came head-to-head with the individualistic Anglo-Saxon cheque-book control approach (which at the time was widely accepted in Australia) whereby often the winning tender was based on the lowest price (over quality).

One such collaboration was Utzon’s work with the Swedish company, Höganäs AB, which produced the very distinctive tiles covering the roof of the Opera House.

A very well documented rift between Utzon and Hughes followed, between the perfectionist and the pragmatist. Utzon’s Nordic craft approach to architecture working closely with other skilled companies who were equally focused on high quality (over cost) came head-to-head with the individualistic Anglo-Saxon cheque-book control approach (which at the time was widely accepted in Australia) whereby often the winning tender was based on the lowest price (over quality).

One such collaboration was Utzon’s work with the Swedish company, Höganäs AB, which produced the very distinctive tiles covering the roof of the Opera House.

utzon's departure

Protests in front of the unfinished opera house

Protests in front of the unfinished opera house

With Hughes at the helm exerting strict control of the ‘cheque book’, Utzon was now no longer being paid up front, only for completed work.

By 1966, Hughes was refusing to pay Utzon’s outstanding fees, which eventually led to Utzon’s letter of withdrawal as Chief Architect in February of that year. Just a few months later, the Australian architects, Peter Hall, Lionel Todd and David Littlemore were announced as the successors to complete the project.

Following Utzon’s letter, there were widespread protests by leading Australian architects, authors, university deans and others demanding his reinstatement. Even at the Public Works Department in the Government architect’s office, 75 out of 85 architects signed a petition to bring Utzon back. However, it all fell on deaf ears.

By 1966, Hughes was refusing to pay Utzon’s outstanding fees, which eventually led to Utzon’s letter of withdrawal as Chief Architect in February of that year. Just a few months later, the Australian architects, Peter Hall, Lionel Todd and David Littlemore were announced as the successors to complete the project.

Following Utzon’s letter, there were widespread protests by leading Australian architects, authors, university deans and others demanding his reinstatement. Even at the Public Works Department in the Government architect’s office, 75 out of 85 architects signed a petition to bring Utzon back. However, it all fell on deaf ears.

The greatest building of the 20th century

|

In the end, 10,000 workers of 90 nationalities over a 14-year period worked on the opera house building. On 20 October 1973, the Sydney Opera House was officially opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II - the same day the Royal Institute of Architects Australia awarded Utzon a gold medal.

Utzon did not return to Sydney to attend these ceremonies. The Sydney Opera House has been hailed as the greatest building of the 20th century, and it put Australia and more specifically Sydney on the world map. When the building was named as a UNESCO world heritage building, the committee making the decision said: It stands by itself as one of the indisputable masterpieces of human creativity, not only in the 20th century but in the history of humankind |

|

Utzon himself later expressed his feelings about the iconic status the building proved to have |

To me it is a great joy to know how much the building is loved, by Australians in general and by Sydneysiders in particular |

utzon's legacy

Daughter Lin Utzon

Daughter Lin Utzon

33 years after leaving the project, Utzon signed a new contract (together with his son Jan) with the NSW government to establish a set of design principles to act as a reference for future architects and designers involved in the building, thereby continuing his vision of the building in centuries to come.

Part of the project also involved the opening of the Utzon Room in 2004, the first authentic Utzon interior as well as working on The Colonnade, the Accessibility and Western Foyers Project.

At the opening of The Colonnade in 2006, Jan Utzon said of his father

Part of the project also involved the opening of the Utzon Room in 2004, the first authentic Utzon interior as well as working on The Colonnade, the Accessibility and Western Foyers Project.

At the opening of The Colonnade in 2006, Jan Utzon said of his father

He is too old by now to take the long flight to Australia. But he lives and breathes the Opera House, and as its creator he just has to close his eyes to see it